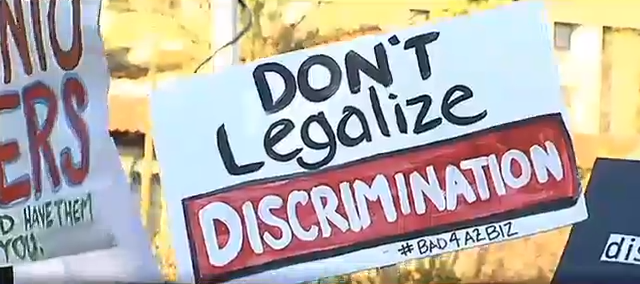

The editorial board of the National Review ripped into “organized homosexuality” for opposing a measure passed by the Arizona legislature that would allow businesses and individuals to deny services to gay couples on religious grounds, defending the bill as part of the “live-and-let-live” credo.

In an editorial published online on February 24, the conservative publication's editors defended the bill as “necessary,” criticizing the “oppression envy” shown by LGBT activists who have opposed the law and rejecting comparisons of the legislation to Jim Crow laws (emphasis added):

It is perhaps unfortunate that it has come to this, but organized homosexuality, a phenomenon that is more about progressive pieties than gay rights per se, remains on the permanent offensive in the culture wars. Live-and-let-live is a creed that the gay lobby specifically rejects: The owner of the Masterpiece Cakeshop in Colorado was threatened with a year in jail for declining to bake a cake for a same-sex wedding. New Mexico photographer Elaine Huguenin was similarly threatened for declining to photograph a same-sex wedding. It is worth noting that neither the baker nor the photographer categorically refuses services to homosexuals; birthday cakes and portrait photography were both on the menu. The business owners specifically objected to participating in a civic/religious ceremony that violated their own consciences.

[...]

Gay Americans, like many members of minority groups, are poorly served by their self-styled leadership. Like feminists and union bosses, the leaders of the nation's gay organizations suffer from oppression envy, likening their situation to that of black Americans -- as though having to find a gay-friendly wedding planner (pro tip: try swinging a dead cat) were the moral equivalent of having spent centuries in slavery and systematic oppression under Jim Crow. Their goal is not toleration or even equal rights but official victim-group status under law and in civil society, allowing them to use the courts and other means of official coercion to impose their own values upon those who hold different values.

Which is to say, what is regrettable here is not Arizona's law but the machinations that have made it necessary. It seems unlikely that those religious bakers and photographers were chosen at random, or that their antagonists will stop until such diversity of opinion as exists about the subject of gay marriage has been put under legal discipline.

The editors' assertion that the measure only targets services related to same-sex marriage has been debunked by experts. As constitutional law professor Kenji Yoshino of New York University has noted, the measure is written broadly enough that any individual or business owner would be allowed to refuse service to any gay person on the grounds that doing business with a gay person imposed a substantial burden on his or her religious beliefs.

Moreover, the argument that serving a cake to a same-sex couple is tantamount to participation in their wedding has been derided as bogus by evangelical writers Jonathan Merritt and Kirsten Powers, who point out that the notion that a vendor is participating in a union didn't arise until marriage equality started taking effect around the country.

And even as the editors attempted to distinguish the Arizona measure from Jim Crow laws targeted at African-Americans, they advanced the very same argument put forth by supporters of those laws - that it's up to individual business owners to decide whom they wish to serve (emphasis added):

One of the defects of our civil-rights law is the overly broad concept of “public accommodation,” which has been expanded to include virtually every business that is open to the public. But a business is not public property; it is private property. People of good will ought to allow fairly broad leeway for how people conduct their own lives and their own business -- private autonomy is, after all, a large part of the case for gay rights. If gay leaders were willing to extend to those who do not share their views the same tolerance to which they feel themselves entitled, then a modus vivendi could emerge through the healthful operations of civil society. Those who do not wish to participate in gay weddings or other events could decline to do so -- and those who believe them to be bigots could take their business elsewhere. In fact, one protester of the Arizona law has precisely the right idea: Outraged by the passage of this bill, a pizza-shop operator hung a sign in his door announcing that members of the state legislature were personae non gratae in his establishment. That, and not the micromanagement of secular divines in black robes, is the way to sort out this kind of social controversy.

National Review's defense of segregated services echoes the magazine's ugly civil rights history. In a notorious 1957 editorial commonly attributed to founder William F. Buckley, the magazine defended Southern laws disenfranchising blacks on the grounds that “for the time being,” whites constituted “the advanced race.” A 1960 editorial stated that in comparison with whites, African-Americans in the Deep South were “retarded.” Buckley greeted the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act with warnings of “chaos” and “mobocratic rule.”

While National Review now seeks to distance itself from the very policies it long encouraged, its willingness to defend the legislation of anti-gay bigotry again places the publication on the wrong side of history.