Health care policy experts are speaking out against Dr. Ben Carson's proposal to replace the Affordable Care Act with a healthcare savings account and $2,000 annual federal stipend, calling it “near worthless” and a plan “for the very rich.”

Health care policy experts are speaking out against Dr. Ben Carson's proposal to replace the Affordable Care Act with a healthcare savings account and $2,000 annual federal stipend, calling it “near worthless” and a plan “for the very rich.”

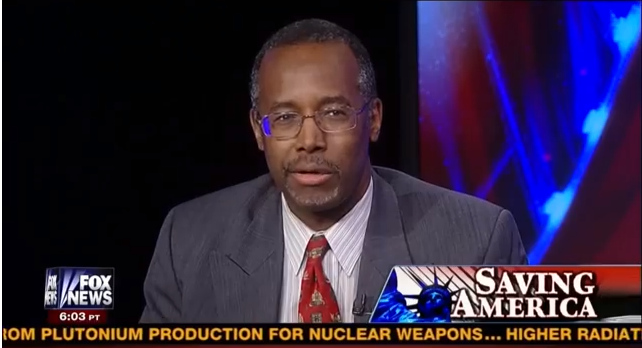

Carson, a retired neurosurgeon and Fox News contributor, is beloved by conservatives for his vitriolic attacks on Obamacare. He has received a raft of recent media attention due to the strong fundraising totals posted by the independent National Draft Ben Carson political action campaign, which promotes a Carson 2016 presidential run.

In an interview with Politico Magazine, Carson says that he supports eliminating Obamacare and that under his plan, “The only responsibility of the government would be providing $2,000 per year for every American citizen -- around $630 billion annually, about 20 percent of what we currently spend on health care -- to provide everyone with a health savings account.”

Carson says the current health care system has created “generation upon generation of people who just live that way, waiting for government handouts.”

But as Politico Magazine notes, while Carson's celebrated medical record “puts weight behind his criticisms of Obamacare,” his acknowledged skill as a surgeon “does not imply an elevated or even rational perspective on health-care policy.”

Indeed, several experts who have studied and formulated health care reforms told Media Matters that the plan, if implemented, could have devastating consequences for millions of Americans.

“For a person who has serious health problems or for a person who has a low income, a $2,000 health care savings account is worthless, or near worthless” said Timothy Jost, professor of law at Washington and Lee University who specializes in health care regulation and law. "It would not either allow them to buy health insurance or allow them to afford health care or anything other than very routine primary care and some medications."

“I wouldn't mind the government giving me $2,000 for a health savings account because I have great health insurance from my employer,” Jost added. “I'm sure if you are a doctor at Johns Hopkins, this is a great idea. You have $2,000 in your pocket. But if you are from the wrong side of Baltimore, it is not going to help very much. It is not going to help you get insurance and not cover more than basic primary care.”

Jonathan Gruber, a health economics expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who advised both Gov. Mitt Romney and President Obama on their health care plans, echoed Jost's concerns, calling Carson's approach “just a plan for the very rich who would not be discriminated against by the insurance market.”

“It's not really insurance,” he added. “It is leaving you self-insured for any risk above $2,000. The typical heart attack in the U.S. can cost about $100,000. This is typical of the poverty of ideas on the right on health care right now.”

Carolyn Engelhard, assistant professor of public health sciences and director of the Health Policy Program at the University of Virginia, agreed.

“There are some good things to be said about health savings accounts, but the downside is that they're applied across the board,” she said. “If someone is low-income but has a lot of medical bills, they are going to have more out of pocket costs than someone who, say, makes $100,000 and is healthy. It is a blunt instrument, it does reduce unnecessary care, but the bad thing is that if the $2,000 is exceeded and your deductible is $6,000, you may not have that extra $4,000 that is needed and go without needed heath care.”

Calling herself a “lukewarm fan” of the Affordable Care Act, Engelhard added that “people who choose HSA's are healthier and have more money to put in their HSA's.” But, she added, if you make $8 per hour “you don't have enough to pay your bills, let alone put extra money into an HSA. Just giving people an HSA and telling them to be smarter about spending is an overly-simplistic method. It won't work well.”

Sabrina Corlette, a senior research fellow at the Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms, agreed that the $2,000 would simply not be enough.

“For starters, it wouldn't come close to covering the cost of health insurance,” she said. “The annual average cost for a family is $15,000 per year, and $8,000 or $9,000 for an individual. It's not going to go very far. You are still left with the problem of people not being able to afford health care and people would not be able to get coverage no matter how much they have if they have a pre-existing condition, or be charged more if you have a condition.”

She called it a "$2,000 handout that doesn't get us very far and doesn't solve many of the systemic problems we have, or improve access to coverage or improve people's health."