How The Rolling Stone Rape Story Failure Has -- And Hasn't -- Changed Media Coverage

Written by Joe Strupp

Published

Three months after a Columbia University investigation found major journalistic errors in a Rolling Stone report on campus sexual assault at the University of Virginia, major news outlets say they have not adjusted their approach to covering similar stories. But rape survivor advocates say they have seen less coverage of the issue since the failures of the Rolling Stone report came to light, and, in some cases, an increased hesitancy in trusting survivors' accounts.

Three months after a Columbia University investigation found major journalistic errors in a Rolling Stone report on campus sexual assault at the University of Virginia, major news outlets say they have not adjusted their approach to covering similar stories. But rape survivor advocates say they have seen less coverage of the issue since the failures of the Rolling Stone report came to light, and, in some cases, an increased hesitancy in trusting survivors' accounts.

The November 2014 Rolling Stone article “A Rape on Campus” prominently featured the story of “Jackie,” a pseudonymous University of Virginia student who told the outlet she was gang-raped in 2012 at a fraternity party.

After initially receiving praise, the article came under fire for an apparent failure to seek comment from the alleged suspects. Other factual questions arose, prompting Rolling Stone to commission an investigation with the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and its dean, Steve Coll.

That investigation, released in early April, found the Rolling Stone story was a “journalistic failure that was avoidable. The failure encompassed reporting, editing, editorial supervision and fact-checking. The magazine set aside or rationalized as unnecessary essential practices of reporting that, if pursued, would likely have led the magazine's editors to reconsider publishing Jackie's narrative so prominently, if at all.”

Though the report outlined specific failures in the Rolling Stone editorial process (while declining to adjudicate exactly what happened to “Jackie”), it also pointed to broader problems in how all outlets cover sexual assault, and offered some suggestions on “how journalists might begin to define best practices when reporting about rape cases on campus or elsewhere.” It recommended, for example, that journalists spend time further deliberating how best to balance sensitivity to victims with the demands of verification, and how best to corroborate survivor accounts.

In interviews with Media Matters, editors from The New York Times, The Washington Post, USA Today and other outlets said they have not adjusted their approach to covering the stories of rape survivors in light of the Rolling Stone mess and the resulting Columbia report.

Several editors said that the Rolling Stone saga would not cause them to believe survivors less or hesitate to publicize their stories.

"I don't think that story holds any larger lessons about rape coverage, or whether one should believe alleged assault victims," New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet told Media Matters via email. “It was a poorly-done story ... It doesn't make me any more or less likely to believe a source. We always verify, get the other side, and report the heck out of a story, no matter the subject.”

Other editors who spoke with Media Matters maintain their coverage will be unaffected.

“It hasn't, or won't change how we view these stories,” said David Callaway, editor of USA Today. “I always thought the idea that news organizations would cut back on their coverage because of one poor example seemed a bit far-fetched. We still get people coming to us with stories or requests for coverage many times a day, and the ones we choose to go after we only pursue if we can verify. We have detailed guidelines on sourcing and fairness in coverage and we have no plans to change those in the wake of the Rolling Stone debacle.”

He added, “Verification is the key. Reporters get lots of tips and listen to lots of tales. Some are true. Some are not. None should be published unless they can be verified and all sides contacted. That hasn't changed.”

For Martin Baron, editor of The Washington Post, the same is true: “Nothing has changed in our coverage. We always try to be both sensitive and careful, and to report such stories thoroughly.”

Colleen Schwartz, a spokesperson for The Wall Street Journal, responded to a request for comment to Journal editor-in-chief Gerard Baker with this statement:

Our journalists take very seriously our tradition at The Wall Street Journal of vetting assertions before they are published, whatever the topic. We discuss and debate journalism practices, standards and ethics as a matter of course at the Journal, but the high bar we set for ourselves for being accurate and fair existed here long before the publication of the Rolling Stone story. We will continue to uphold our same rigorous standards, irrespective of the Rolling Stone article.

Robert Rosenthal, executive director of the Center for Investigative Reporting, said via email, “This is very sensitive and difficult reporting and the Rolling Stone incident did not teach us anything except to rely on the standards and practices CIR has maintained for 37 years when it comes to verification for all of our work. And to do everything we can to make sure we are fair in our conclusions and that they are based on facts and sources who are named, not anonymous.”

Asked specifically if the Rolling Stone story would prompt his reporters to question rape survivors more, he said, “I think the issue of veracity with any source is something we discuss and think about on any story. Understanding the potential motivations of any source on any story is something I was taught very early on in my career and we think about it at CIR especially if someone is alleging negative or damaging things about an individual or an organization. Allegations about sexual abuse brought by a victim are painful to hear and deal with but bring a great responsibility to do the right thing for all who might be touched by the story.”

Greg Moore, editor of The Denver Post, said the Rolling Stone episode is a “cautionary tale.”

"The Rolling Stone debacle is not going to affect how we deal with allegations of rape," Moore said, calling it, “a reminder that journalists need to always verify information before publishing. That is our practice in print and online. Things like what happened to Rolling Stone occur when you don't follow your reporting and editing procedures.” He concluded, “If anything, we have reminded people to question how we know what we think we know. Regarding allegations of rape, we always want to be sensitive and fair and we will continue to be.”

Audrey Cooper, editor-in-chief of the San Francisco Chronicle, said the focus should be on the treatment of anonymous sources, not “whether to believe alleged victims.”

“It's about how you treat and prosecute (for lack of a better term) anonymous sources,” she said. “We have strong and longstanding policies on anonymous sources, and I am confident those policies would prevent publication of similarly flawed stories.”

Ed Wasserman, dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley, remains concerned.

“It would be unrealistic to say this doesn't cast a shadow over cases like this,” he told Media Matters. “The danger there is that these will be viewed as squalid, inconclusive and very difficult to report with a whole lot of institutional downsides. There are realities that are very difficult to report on while respecting evidentiary standards that journalists adhere to. You can't read the Columbia account of what Rolling Stone did without wincing at the failure to follow rudimentary journalist standards.”

“I think that some news organizations will definitely shy away from these stories,” he concluded, “because they don't have the chops to handle them and they are mindful that they will end up with something that is both squalid and inconclusive.”

While most outlets were confident the Rolling Stone fiasco would not change coverage, some rape survivor advocates and support groups contend the Rolling Stone failures have created a backlash against survivors' stories that is already being felt.

One lawyer who handles such cases for survivors said fewer reporters are coming to her for comment and perspective on campus rape, and that she has also seen journalists scrutinize cases and survivor accounts more than in the past.

“It went from three calls a day to maybe three calls a week, we are seeing a big downturn, less interest in covering it,” said Laura Dunn, an attorney and founder of SurvJustice. “It is not completely devastating to the movement, but you are seeing more focus on the accused.”

Dunn said she has seen a clear impact on reporting: “It has changed how some news media report on the story. I have had one journalist [for whom] it did not matter that I was a lawyer and I had documentation, he wanted someone to independently verify my involvement [in a particular case]. I ended up not working with that journalist.”

Jamia Wilson, executive director of Women Action and the Media, another advocacy group, claimed she has seen a decline in overall media coverage of the issue since the Rolling Stone debacle. “I have not seen as much coverage on the issue. I don't think the volume of coverage has been as much.”

Wilson was also critical of media outlets for not seeking to change their approach for the better. “It's really sad and disappointing to hear them say there won't be changes,” she said.

Karin Roland, organizing director of UltraViolet, a women's rights group that focuses on such issues, said Rolling Stone's “shoddy journalism” hurt survivors' believability, adding “that is a grave disservice to the survivor in question, to all survivors and all students at that school who had a chance to shine a light on a major problem.”

She said the fallout is being felt: “In the back of people's minds there is a question of whether they can believe survivors or not.”

Part of the problem, according to some women's advocacy groups, are the stories of rape news outlets choose to investigate in the first place.

“To me, the worst aspect of the Rolling Stone article was the fact that the magazine and the author insisted on telling the most salacious story they could find, the most outrageous, the most sensationalistic story of rape they could find,” said Terry O'Neill, president of the National Organization for Women. “They worked directly with the head of the student group that advocates around sexual assaults, but they didn't [use many of those stories] and my understanding is that the less sensationalist stories were abundant. I think that right there tells you what's wrong with coverage of sexual assault in the United States today.”

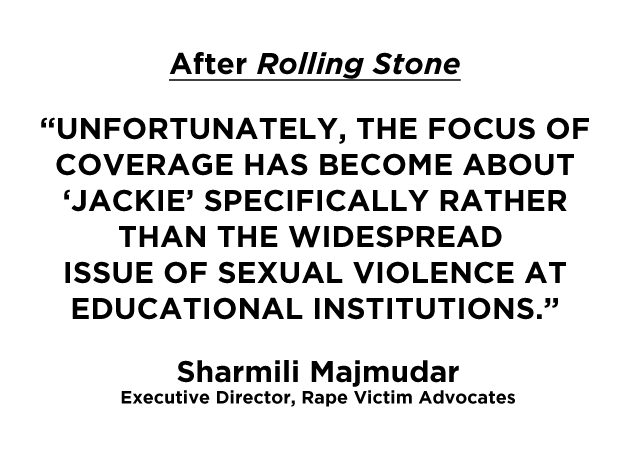

Sharmili Majmudar, executive director of Rape Victim Advocates, said the lesson from Rolling Stone should be how rape and sexual assault are handled by law enforcement and campus officials.

“Lost in the aftermath is the fact that universities routinely discourage reporting of sexual violence, and respond poorly to such reporting when it does occur, as evidenced by the Title IX investigations currently underway at over 100 colleges and universities,” she said. “Unfortunately, the focus of coverage has become about 'Jackie' specifically rather than the widespread issue of sexual violence at educational institutions.”

Media Matters has previously documented how media's failings and inconsistencies when it comes to reporting on sexual assault -- particularly in conservative media, though the trend extends to the mainstream -- can reinforce the stigmas against survivors and discourage victims from reporting these crimes in the first place. Survivors have repeatedly said that the fear that no one will believe them keeps them from speaking out, while some feel re-victimized by the suggestion from media figures that they are lying about the traumatic events they experienced.

As the Columbia report explained, “journalists are rarely in a position to prove guilt or innocence in rape.” But it is a matter of public interest to report on how institutions handle -- or mishandle -- the accusations, and Rolling Stone's failure “draws a map of how to do better.”