Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby argued that LGBT workers don't need the protections afforded by the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), falsely asserting that the free market already provides an adequate check on workplace discrimination.

In his November 17 column, Jacoby noted that many Fortune 500 companies and prominent business leaders including Apple CEO Tim Cook have spoken out against LGBT employment discrimination. Reprising a common argument against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Jacoby contended that businesses should be free to decide whether to discriminate against LGBT people. In Jacoby's view, the fact that many businesses don't do so is sufficient to obviate the need for ENDA (emphasis added):

APPLE CEO Tim Cook, writing recently in The Wall Street Journal, urged Congress to pass the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, or ENDA, which would make it illegal under federal law for employers to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Prejudice, Cook insisted, is bad for business. Indeed it is -- as defenders of free markets have pointed out for years, irrational discrimination tends to reduce an employer's profits. Far from strengthening the case for a new federal law, however, it seems to me that Cook's observation cuts the other way.

Thanks to the changes already produced by the marketplace, a significant addition to the Civil Rights Act is superfluous. According to the Human Rights Campaign, the influential gay-rights organization and a prominent supporter of ENDA, nearly 90 percent of companies in the Fortune 500 have explicitly banned employment discrimination against gays and lesbians. As of April, only about 60 companies on Fortune's list had not yet formally adopted such policies, and very few have actually voted against doing so.

[...]

Clearly there has been a sea change in the way Americans have come to think about employment discrimination against gays and lesbians. It would be surprising if that change weren't reflected on payday -- and sure enough, that's what the data show. Economists Geoffrey Clarke and Purvi Sevak, in a study just published in the journal Economic Letters, note that gay men in the 1980s and early 1990s had less earning power than straight men of comparable age, race, and education. By the mid-1990s that “gay wage penalty” had disappeared; in the years since 2000 it has turned into a wage premium. As far back as 2002, for example, gay men were outearning their nongay peers by 2.45 percent.

Is it logical to conclude from all this that the American workplace is so poisoned with bigotry against gays and lesbians that only a drastic change in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 can end the oppression? Or would it be fairer to say that the vast majority of American workers have no desire to see colleagues hired or fired because of their sexual orientation -- and that the vast majority of US companies have no interest in letting sexual orientation become an issue? For years opinion surveys have documented near-universal support for gay rights in the workplace. The market is doing what markets have always sought to do: break down unreasonable discrimination by making it unhealthy for a business's bottom line.

New federal laws should be a last resort, when there is no other means of solving an urgent national problem. In a country of 300 million people, there will always be occasional incidents of bigotry and unfairness directed at people where they work, but plainly there is no urgent crisis in the treatment of gay and lesbian employees that Congress alone can fix. As it is, 21 states and nearly 200 cities and counties have followed the market's lead and enacted legislation barring employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Washington has more than enough on its plate. It doesn't need to add yet another protected category to the list of groups legally protected from private discrimination. That will only make federal cases out of even more disputes.

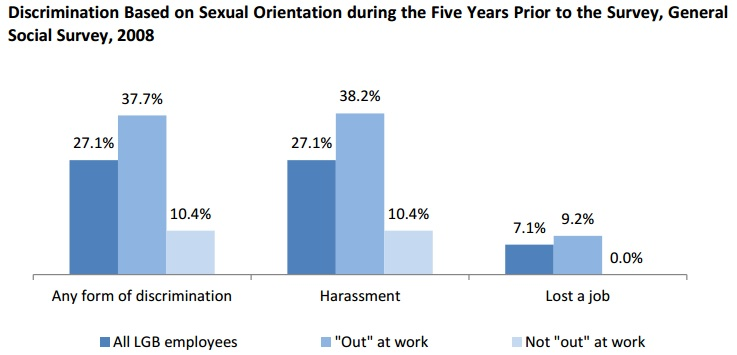

There's no denying that the cultural shift in attitudes toward LGBT people has spurred many companies to implement non-discrimination policies for LGBT workers. That doesn't change the reality that it's still perfectly legal to fire an employee for being gay in 29 states and that 33 states have no protections for transgender workers. As a 2011 study by UCLA's Williams Institute found, LGBT employees continue to experience “widespread discrimination” in the workplace:

Moreover, Jacoby's claim about pay for gay workers is misleading. According to the Williams Institute, gay men earn between 10 and 32 percent less than similarly educationally and professionally qualified heterosexual men. A 2013 Experian study, meanwhile, found that lesbian women, on average, earn nearly 9 percent less than heterosexual women. Transgender workers face an even harsher reality, with nearly two-thirds earning incomes below $25,000, according to the American Psychological Association.

Jacoby's analysis of ENDA's impact on litigation is equally flawed. While he implies that ENDA will trigger a new wave of “federal cases,” the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects a modest 5 percent increase in the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's workload as a result of ENDA.

Unwittingly, Jacoby actually makes an excellent argument for ENDA when he inveighs against the creation of “yet another protected category.” If Jacoby published a column in 2013 championing the right of businesses to refuse to hire African-Americans, he would undoubtedly generate a significant public backlash. That Jacoby feels comfortable arguing that LGBT workers should be subject to the whims of their employers' personal views says much about the need to end LGBT employment discrimination.